I always travel with a pair of rock climbing shoes, small, narrow rubber and leather lace-ups that hurt my feet. It’s a sport I often practiced before the pandemic shut down all the climbing gyms that I happily rediscovered on my Christmas break. It’s the best possible land-based complement to windsurfing and a recommended workout for everyone. Here’s why.

The sport of rock climbing broadly divides up into outdoor and indoor, with ropes and without. Outdoor rock climbing is the original (and to some, the only real) discipline. I’ve done it, but not often, because it takes time, specialized equipment and a climbing partner, none of which I usually have on hand. But if you get the chance and have the time, try it, because it feels like a real adventure.

The few times I’ve climbed outdoors have been with family, an annual day trip to the rocks around our summer holiday home in Provence. I pack up ropes, harnesses, carabiners and sun screen, and with a sibling or two, we take my daughters, Alison and Eliza, and all the nieces and nephews climbing. In a summer camp-like mood, we walk single-file through the wilderness to find a climbable rock wall, somehow never finding the one from last year. Then, playing camp counselor, I set up the rope, rappel down, mindful not to ruin the day by falling catastrophically, triple check everything, and check once more, then push, pull and cajole each young climber up the rock face, ending with the even harder task of getting them down, a lesson in trusting the rope.

It’s useful to introduce children early. Climbing, like skiing, is a sport that involves heights and hard surfaces. A fear of falling is normal and children overcome that fear faster than adults, building their confidence for future activities.

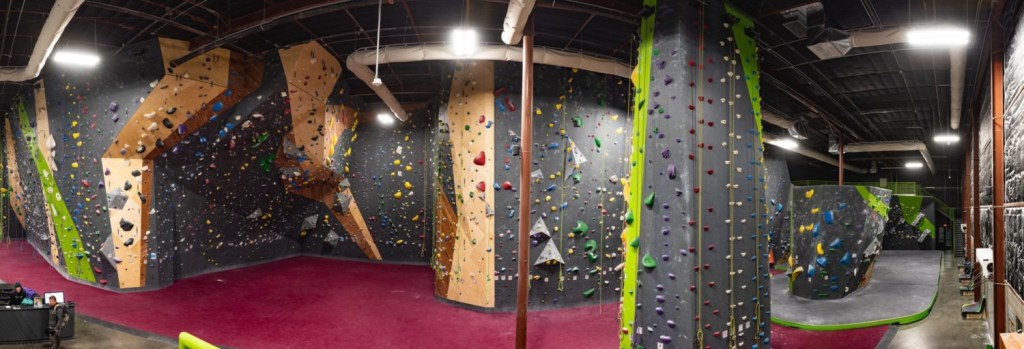

Indoor climbing (notice that I dropped the rock, for the purists out there) is notably easier. Drive up to a climbing gym, which are now everywhere, bring or rent shoes and a harness, and off you go.

You can take the easy-hard option or the hard-easy option. Easy-hard is climbing without ropes on short routes. It’s easy to get started, requires no harness or ropes, no partner, no training; but it’s hard work and slow progress. Hard-easy is climbing with ropes. It’s hard to get started, learning the equipment and safety rules, and requires a partner (nowadays an auto-belay is a viable alternative, but not quite as social), and the heights can be scary; but it’s easier to make progress and arguably more rewarding. Both options deliver a world-class workout and much more besides.

Let me start by describing a typical roped session (the hard-easy option). I’ll use my last session as an example, accompanied by my daughter. We had not climbed in a couple of years, so we asked for an orientation, fifteen minutes on how to use a harness, tie yourself to the rope, use a belay (a device to hold the rope), and support the climber. This was a valuable refresher as some of my habits are now considered “old school” (in the words of our twenty-something instructor); you’re never too “old” to learn new tricks.

Now we’re ready to hit the walls. Climbing with ropes is mostly done on routes, preset paths up the wall or rock face. The difficulty of each route depends on its gradient and holds. More vertical or overhanging is harder, putting more weight on your hands and arms. Smaller holds spaced further apart are harder, again putting more strain on hands and arms. In fact, I would summarize the art of rock climbing as the mastery of using feet and legs over hands and arms. This takes balance, technique and patience, not brute force, which could explain why the sport is so popular with women, and why they do so well.

I start on belay, supporting my daughter. This is a top-rope route, so the rope is wrapped over a bar (or ring) at the top of the wall. I clip into the belay on one end and my daughter ties herself to the other end. Top-roping is much easier than the alternative, which is for the climber to carry the rope up the wall while climbing (which is called leading), clipping the rope into rings along the way, which will hold them in case of a fall. Both techniques use someone on belay, to pull in the rope when top-roping and to let out the rope when the climber is leading. Definitely start with top-rope routes.

Climbing is the hard part, but belaying is the important part. The belayer keeps the climber alive by holding the rope on the way up, in case of fall, and then lowering them down. It takes a a lot of faith to trust that the long chain of dependencies will hold; the harness webbing (not worn out) tied around your waist (securely), which is tied tied to the rope (correctly), sliding (smoothly) through the top ring (secured), clipped into the belay device (so small and light), tied (correctly) into the belayer’s harness (not worn out), who is holding the rope just right (with both hands in the proper position), and paying attention (not admiring the scenery)… but after a few climbs you forget all that, trust that it all works, and start to enjoy the physical challenge.

We exchange the customary safety checks: Belay on? On Belay! Climbing. Climb on! She climbs confidently. My job is to take the slack out of the rope so that if she falls she doesn’t fall far, and to always be ready for a fall; it’s all about the fall! I synchronize with her climbing, adjusting the rope to each of her moves while keeping my hands in the optimal holding (brake) position, just in case. She’s quick to the top and I lower her to the floor.

Now it’s my turn to climb. I take my first step up the wall, finding the holds that will put me in the most comfortable position (weight perfectly centered over my feet) and give me the easiest path to the next hold (using my legs as much as possible). Each move is both a creative and physical endeavor. Among the many possibilities there is the perfect way to climb this route, for someone of my height and ability, if I can only find it; every climber carves their own path. And in all cases it’s going to be exhausting because humans are simply not well designed to climb vertical walls (quite unlike a spider). The beauty of rock climbing is exploring the infinite possibilities of movement, a minuscule rotation of the foot or knee, the imperceptible drop of a hip, the slight shift of emphasis between finger and thumb, under intense physical and emotional duress.

Every route has a crux, the most difficult move, which turns every route into a hero’s journey. On this route, mine was half way up. I was feeling pretty good with myself until then, the holds magically materizaling where I hoped they would be, drawing me up the wall. And then a gap, no obvious or natural move. I shift my weight this way and that, looking for options, testing different possibilities. My toes, anchoring me to the wall, are tiring. My fingers and arms are numbing. I must move soon or fall. And knowing that this move requires total commitment, that once started it must be completed, I let one foot hang, straighten the other leg, crimp the opposite hand, and slowly, oh so carefully, reach for the impossibly angled hold way out of reach. Not carefully enough though. My fingers slip and I’m instinctively flailing against the momentary weightless drop, until the rope catches, holds and I sit there, swaying in my harness, shaking from the effort. But then I reach out to the wall, get myself back on, try again, a different angle, more engagement, more faith, and eventually succeed, and I feel great, really great, knowing I reached my limits and overcame them, all packed into a five minute exercise. I’m elated as I’m lowered, victorious, floating high above the adulating onlookers (at least in my adrenaline-soaked mind).

Indoor routes for climbing with ropes are around 10 meters high (33 feet) and are graded for difficulty from 5.4 to 5.15 plus in the US (other countries use different scales). A beginner can quickly move up three or four grades, which is motivating. After a couple of years of regular practice you can expect to climb 5.10 and higher, at which point each grade is subdivided into a, b, c and d and progress is slower. After 15 years of irregular practice I plateaued at 5.11b with two thirds of the grading scale still ahead of me.

Routes you can climb without ropes, called bouldering, are less than half the height, though it feels higher when you’re at the top, untethered, hanging on by your fingernails. A fall onto the padded floor might hurt but not too much. Bouldering routes are graded from V0 to V16 plus in the US. On these short routes, every hold is significant, positioned for maximum challenge. Some routes might only have a half-dozen in total. Each move feels like a choreographed dance, gracefully contorting your body and limbs to the intended design of the route setter (the genius sadist that laid out the holds on the wall). It’s intense work, requiring lots of repetition, strengthening and atuning with your body, not unlike yoga in its physical and spiritual dimensions. A beginner will struggle with VO and V1 for a while and might reach V5 after several years, the upper limit for most amateurs. It takes relentless dedication to get beyond that, the difference between a pastime and a passion.

I love climbing, the challenge, the focus, the excitement. It’s a head-to-toe workout for the body packaged into a zen-like experience for the mind. Only other passions (read windsurfing) keep me from giving it more time. I encourage you to try, and maybe make it your passion.